The outermost layer of your operating system – the part you interact with – is called the shell. Fedora comes with several preinstalled shells. Shells can be either graphical or text-based. In documentation, you will often see the acronyms GUI (Graphical User Interface) and CLI (Command-Line Interface) used to distinguish between graphical and text-based shells/interfaces. Other GUI and CLI shells can be used, but GNOME is Fedora’s default GUI and Bash is its default CLI.

The remainder of this article will cover recommended dotfile practices for the Bash CLI.

Bash overview

From the Bash reference manual:

At its base, a shell is simply a macro processor that executes commands. The term macro processor means functionality where text and symbols are expanded to create larger expressions.

Reference Documentation for Bash

Edition 5.0, for Bash Version 5.0.

May 2019

In addition to helping the user start and interact with other programs, the Bash shell also includes several built-in commands and keywords. Bash’s built-in functionality is extensive enough that it is considered a high-level programming language in its own right. Several of Bash’s keywords and operators resemble those of the C programming language.

Bash can be invoked in either interactive or non-interactive mode. Bash’s interactive mode is the typical terminal/command-line interface that most people are familiar with. GNOME Terminal, by default, launches Bash in interactive mode. An example of when Bash runs in non-interactive mode is when commands and data are piped to it from a file or shell script. Other modes of operation that Bash can operate in include: login, non-login, remote, POSIX, unix sh, restricted, and with a different UID/GID than the user. Various combinations of these modes are possible. For example interactive+restricted+POSIX or non-interactive+non-login+remote. Which startup files Bash will process depends on the combination of modes that are requested when it is invoked. Understanding these modes of operation is necessary when modifying the startup files.

According to the Bash reference manual, Bash …

1. Reads its input from a file …, from a string supplied as an argument to the -c invocation option …, or from the user’s terminal.

2. Breaks the input into words and operators, obeying [its] quoting rules. … These tokens are separated by metacharacters. Alias expansion is performed by this step.

3. Parses the tokens into simple and compound commands.

4. Performs the various shell expansions …, breaking the expanded tokens into lists of filenames … and commands and arguments.

5. Performs any necessary redirections … and removes the redirection operators and their operands from the argument list.

6. Executes the command.

7. Optionally waits for the command to complete and collects its exit status.

Reference Documentation for Bash

Edition 5.0, for Bash Version 5.0.

May 2019

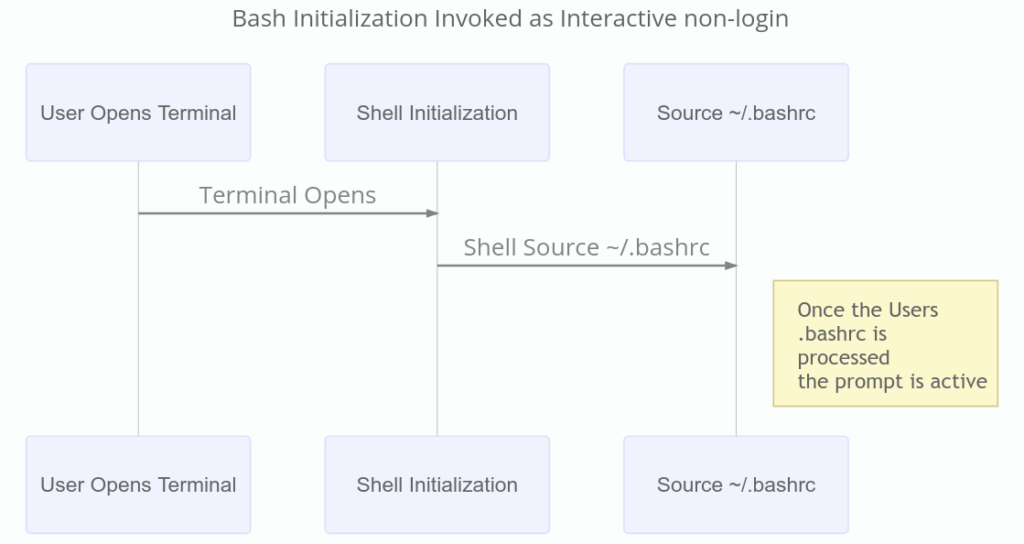

When a user starts a terminal emulator to access the command line, an interactive shell session is started. GNOME Terminal, by default, launches the user’s shell in non-login mode. Whether GNOME Terminal launches the shell in login or non-login mode can be configured under Edit → Preferences → Profiles → Command. Login mode can also be requested by passing the –login flag to Bash on startup. Also note that Bash’s login and non-interactive modes are not exclusive. It is possible to run Bash in both login and non-interactive mode at the same time.

Invoking Bash

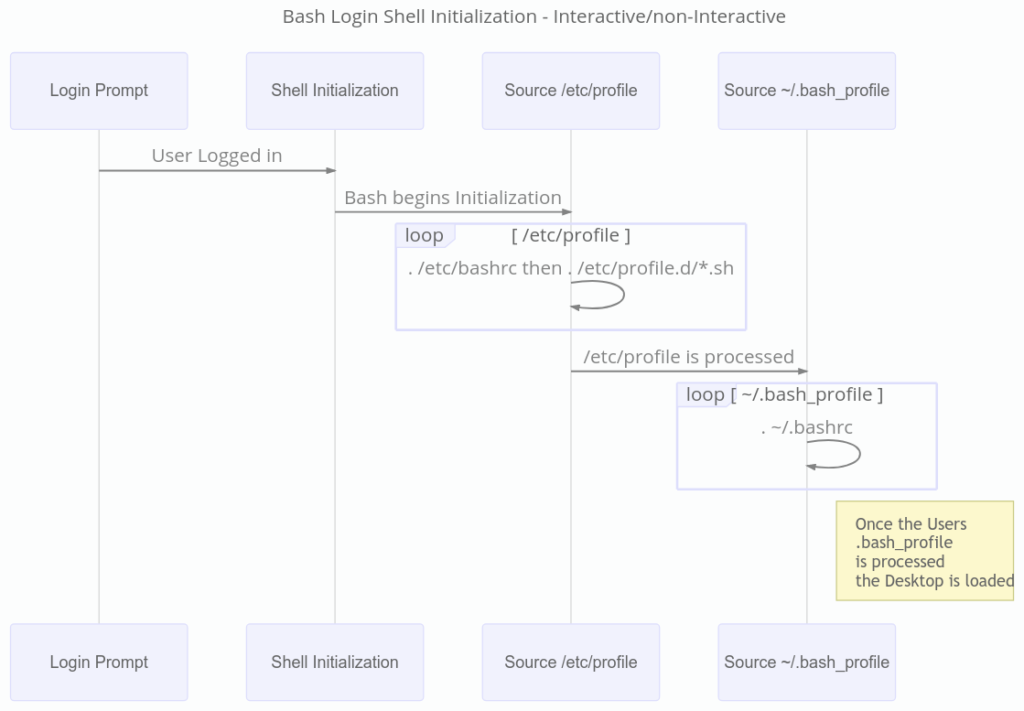

Unless it is passed the —noprofile flag, a Bash login shell will read and execute the commands found in certain initialization files. The first of those files is /etc/profile if it exists, followed by one of ~/.bash_profile, ~/.bash_login, or ~/.profile; searched in that order. When the user exits the login shell, or if the script calls the exit built-in in the case of a non-interactive login shell, Bash will read and execute the commands found in ~/.bash_logout followed by /etc/bash_logout if it exists. The file /etc/profile will normally source /etc/bashrc, reading and executing commands found there, then search through /etc/profile.d for any files with an sh extension to read and execute. As well, the file ~/.bash_profile will normally source the file ~/.bashrc. Both /etc/bashrc and ~/.bashrc have checks to prevent double sourcing.

An interactive shell that is not a login shell, will source the ~/.bashrc file when it is first invoked. This is the usual type of shell a user will enter when opening a terminal on Fedora. When Bash is started in non-interactive mode – as it is when running a shell script – it will look for the BASH_ENV variable in the environment. If it is found, will expand the value, and use the expanded value as the name of a file to read and execute. Bash behaves just as if the following command were executed:

if [ -n "$BASH_ENV" ]; then . "$BASH_ENV"; fi

It is important to note that the value of the PATH variable is not used to search for the filename.

Important user-specific dotfiles

Bash’s best-known user dotfile is ~/.bashrc. Most user customization is done by editing this file. Most user customization, may be a stretch since there are reasons to modify all of the mentioned files; as well as other files that have not been mentioned. Bash’s environment is designed to be highly customizable in order to suit the needs of many different users with many different tastes.

When a Bash login shell exits cleanly, ~/.bash_logout and then /etc/bash_logout will be called if they exist. The next diagram is a sequence diagram showing the process Bash follows when being invoked as an interactive shell. The below sequence is followed, for example, when the user opens a terminal emulator from their desktop environment.

Armed with the knowledge of how Bash behaves under different invocation methods, it becomes apparent that there are only a few typical invocation methods to be most concerned with. These are the non-interactive and interactive login shell, and the non-interactive and interactive non-login shell. If global environment customizations are needed, then the desired settings should be placed in a uniquely-named file with a .sh extension (custom.sh, for example) and that file should be placed in the /etc/profile.d directory.

The non-interactive, non-login invocation method needs special attention. This invocation method causes Bash to check the BASH_ENV variable. If this variable is defined, the file it references will be sourced. Note that the values stored in the PATH environment variable are not utilized when processing BASH_ENV. So it must contain the full path to the file to be sourced. For example, if someone wanted the settings from their ~/.bashrc file to be available to shell scripts they run non-interactively, they could place something like the following in a file named /etc/profile.d/custom.sh …

# custom.sh . . . #If Fedora Workstation BASH_ENV="/home/username/.bashrc" . . . #If Fedora Silverblue Workstation BASH_ENV="/var/home/username/.bashrc" export BASH_ENV

The above profile drop-in script will cause the user’s ~/.bashrc file to be sourced just before every shell script is executed.

Users typically customizie their system environment so that it will better fit their work habits and preferences. An example of the sort of customization that a user can make is an alias. Commands frequently run with the same set of starting parameters are good candidates for aliases. Some example aliases are provided in the ~/.bashrc file shown below.

# .bashrc # Source global definitions if [ -f /etc/bashrc ]; then . /etc/bashrc fi . . . # User specific aliases and functions alias ls='ls -hF --color=auto' alias la='ls -ahF --color=auto' # make the dir command work kinda like in windows (long format) alias dir='ls --color=auto --format=long' # make grep highlight results using color alias grep='grep --color=auto'

Aliases are a way to customize various commands on your system. They can make commands more convenient to use and reduce your keystrokes. Per-user aliases are often configured in the user’s ~/.bashrc file.

If you find you are looking back through your command line history a lot, you may want to configure your history settings. Per-user history options can also be configured in ~/.bashrc. For example, if you have a habit of using multiple terminals at once, you might want to enable the histappend option. Bash-specific shell options that are boolean in nature (take either on or off as a value) are typically enabled or disabled using the shopt built-in command. Bash settings that take a more complex value (for example, HISTTIMEFORMAT) tend to be configured by assigning the value to an environment variable. Customizing Bash with both shell options and environment variable is demonstrated below.

# Configure Bash History # Expand dir env vars on tab and set histappend shopt -s direxpand histappend # - ignoreboth = ignorespace and ignoredup HISTCONTROL='ignoreboth' # Controls the format of the time in output of `history` HISTTIMEFORMAT="[%F %T] " # Infinite history # NB: on newer bash, anything < 0 is the supported way, but on CentOS/RHEL # at least, only this works HISTSIZE= HISTFILESIZE= # or for those of us on newer Bash HISTSIZE=-1 HISTFILESIZE=-1

The direxpand option shown in the example above will cause Bash to replace directory names with the results of word expansion when performing filename completion. This will change the contents of the readline editing buffer, so what you typed is masked by what the completion expands it to.

The HISTCONTROL variable is used to enable or disable some filtering options for the command history. Duplicate lines, lines with leading blank spaces, or both can be filtered from the command history by configuring this setting. To quote Dusty Mabe, the engineer I got the tip from:

ignoredup makes history not log duplicate entries (if you are running a command over and over). ignorespace ignores entries with a space in the front, which is useful if you are setting an environment variable with a secret or running a command with a secret that you don’t want logged to disk. ignoreboth does both.

Dusty Mabe – Redhat Principle Software Engineer, June 19, 2020

For users who do a lot of work on the command line, Bash has the CDPATH environment variable. If CDPATH is configured with a list of directories to search, the cd command, when provided a relative path as its first argument, will check all the listed directories in order for a matching subdirectory and change to the first one found.

# .bash_profile # set CDPATH CDPATH="/var/home/username/favdir1:/var/home/username/favdir2:/var/home/username/favdir3" # or could look like this CDPATH="/:~:/var:~/favdir1:~/favdir2:~/favdir3"

CDPATH should be updated the same way PATH is typically updated – by referencing itself on the right hand side of the assignment to preserve the previous values.

# .bash_profile # set CDPATH CDPATH="/var/home/username/favdir1:/var/home/username/favdir2:/var/home/username/favdir3" # or could look like this CDPATH="/:~:/var:~/favdir1:~/favdir2:~/favdir3" CDPATH="$CDPATH:~/favdir4:~/favdir5"

PATH is another very important variable. It is the search path for commands on the system. Be aware that some applications require that their own directories be included in the PATH variable to function properly. As with CDPATH, appending new values to PATH can be done by referencing the old values on the right hand side of the assignment. If you want to prepend the new values instead, simply place the old values ($PATH) at the end of the list. Note that on Fedora, the list values are separated with the colon character (:).

# .bash_profile # Add PATH values to the PATH Environment Variable PATH="$PATH:~/bin:~:/usr/bin:/bin:~/jdk-13.0.2:~/apache-maven-3.6.3" export PATH

The command prompt is another popular candidate for customization. The command prompt has seven customizable parameters:

PROMPT_COMMAND If set, the value is executed as a command prior to issuing each primary prompt ($PS1).

PROMPT_DIRTRIM If set to a number greater than zero, the value is used as the number of trailing directory components to retain when expanding the \w and \W prompt string escapes. Characters removed are replaced with an ellipsis.

PS0 The value of this parameter is expanded like PS1 and displayed by interactive shells after reading a command and before the command is executed.

PS1 The primary prompt string. The default value is ‘\s-\v\$ ‘. …

PS2 The secondary prompt string. The default is ‘> ‘. PS2 is expanded in the same way as PS1 before being displayed.

PS3 The value of this parameter is used as the prompt for the select command. If this variable is not set, the select command prompts with ‘#? ‘

PS4 The value of this parameter is expanded like PS1 and the expanded value is the prompt printed before the command line is echoed when the -x option is set. The first character of the expanded value is replicated multiple times, as necessary, to indicate multiple levels of indirection. The default is ‘+ ‘.

Reference Documentation for Bash

Edition 5.0, for Bash Version 5.0.

May 2019

An entire article could be devoted to this one aspect of Bash. There are copious quantities of information and examples available. Some example dotfiles, including prompt reconfiguration, are provided in a repository linked at the end of this article. Feel free to use and experiment with the examples provided in the repository.

Conclusion

Now that you are armed with a little knowledge about how Bash works, feel free to modify your Bash dotfiles to suit your own needs and preferences. Pretty up your prompt. Go nuts making aliases. Or otherwise make your computer truly yours. Examine the content of /etc/profile, /etc/bashrc, and /etc/profile.d/ for inspiration.

Some comments about terminal emulators are fitting here. There are ways to setup your favorite terminal to behave exactly as you want. You may have already realized this, but often this modification is done with a … wait for it … dotfile in the users home directory. The terminal emulator can also be started as a login session, and some people always use login sessions. How you use your terminal, and your computer, will have a bearing on how you modify (or not) your dotfiles.

If you’re curious about what type session you are in at the command line the following script can help you determine that.

#!/bin/bash case "$-" in (*i*) echo This shell is interactive ;; (*) echo This shell is not interactive ;; esac

Place the above in a file, mark it executable, and run it to see what type of shell you are in. $- is a variable in Bash that contains the letter i when the shell is interactive. Alternatively, you could just echo the $- variable and inspect the output for the presence of the i flag:

$ echo $-

Reference information

The below references can be consulted for more information and examples. The Bash man page is also a great source of information. Note that your local man page is guaranteed to document the features of the version of Bash you are running whereas information found online can sometimes be either too old (outdated) or too new (not yet available on your system).

https://opensource.com/tags/command-line

https://opensource.com/downloads/bash-cheat-sheet

You will have to enter a valid email address at the above site, or sign up, to download from it.

https://opensource.com/article/19/12/bash-script-template

Community members who provided contributions to this article in the form of example dotfiles, tips, and other script files:

- Micah Abbott – Principal Quality Engineer

- John Lebon – Principal Software Engineer

- Dusty Mabe – Principal Software Engineer

- Colin Walters – Senior Principal Software Engineer

A repository of example dotfiles and scripts can be found here:

https://github.com/TheOneandOnlyJakfrost/bash-article-repo

Please carefully review the information provided in the above repository. Some of it may be outdated. There are many examples of not only dotfiles for Bash, but also custom scripts and pet container setups for development. I recommend starting with John Lebon’s dotfiles. They are some of the most detailed I have seen and contain very good descriptions throughout. Enjoy!

Esc

Respect, wow

Duke

Engineering precision. Nice job!

Vernon Van Steenkist

A couple of my favorites.

set -o vi

This command puts your shell in vi keybindings mode (normally it is in Emacs keybindings mode). Especially useful if you use a keyboard that doesn’t have arrow keys like an IPhone or IPad. Good quick tutorial and references at

https://catonmat.net/bash-vi-editing-mode-cheat-sheet

Automatically add sub-directories to your PATH

export PATH=$PATH$(find $HOME/.scripts -not ( -name CVS -prune ) -type d -printf “:%p”)

This command adds all the sub-directories in $HOME/.scripts which contain my personal scripts to my PATH while excluding the CVS version control directories.

Also, if you quickly don’t want to run the alias version of a command, just put a backslash in front of it. For example

\ls

will output a directory listing without all the color etc directives that you put in you alias version of ls.

geirha

Never export CDPATH! You’ll get some unpleasant surprises when a script using cd accidentally hits a path from CDPATH

Stephen Snow

Hello @geirha,

Thank you for the information. Could you possibly elaborate on the “unpleasant surprises” for everyone’s edification?

Stephen

geirha

Sorry, I meant to link to the pitfalls page. Here:

https://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashPitfalls#pf48

In short, if cd gets a hit in CDPATH, it will output the absolute path of the directory it ends up in (to alert the user it “ended up” elsewhere), which causes breakage if a script is using cd as part of a command substitution

Stephen Snow

Hello,

Thanks for the link. I corrected the article to reflect your advice. I could see this being a problem under certain situations.

geirha

You should also move it to .bashrc. .bash_profile is only meant to be read during login, so it’s mainly useful for setting environment variables like PATH, not for setting variables that configure your interactive session like HISTSIZE, PS1 and CDPATH.

Jan

Hi Stephen,

geirha possibly refers to the following:

https://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashPitfalls#export_CDPATH.3D.:.2BAH4-.2FmyProject

Stephen Snow

Thank you @Jan,

I think exporting CDPATH is fine since the potential error would really be a problem of the script writer as opposed to a problem with CDPATH being exported. The script writer should never assume anything about the environment of the system beforehand. When I write scripts for a specific function on my system, I know the environment and write with that in mind, but not so for generic scripts I am sharing with others. Therefore I then have to account for the potential pitfalls within the script or with specific instructions on how to use it.

Steve

Additionally, always have “.” as the first component of your CDPATH variable, else you shall see surprising behaviour (eg; you have, ~/images and CDPATH=~/Projects/. Now, if you are in ~ and do ‘cd images’ you will end up in ~/Projects/images, if it exists)

Robin Meade

I like how the author followed the best practice of putting PATH customizations in

, which is where Fedora always put them prior to this commit: https://src.fedoraproject.org/rpms/bash/c/739b272e5f5d10cf27a847a44d09eb7f4b6ec89b?branch=master

Gregory Bartholomew

Putting PATH in the login profile makes more sense to me as well. Especially when you understand that environment variables are always inherited by sub-processes. It is inefficient and you shouldn’t need to recreate or redefine a bunch of variables every time you spawn a shell. Doing that is also quite error-prone as can be seen from commit https://src.fedoraproject.org/rpms/bash/c/e3b3cd9cec4a3bd12a792536c0ea131f5ba5bd72?branch=master.

I also don’t like that /etc/bashrc gets sourced from /etc/profile or that everything under /etc/profile.d gets sourced by both /etc/profile and /etc/bashrc. Everything sourcing everything else, multiple times, seems like a bit of an inefficient mess. And I’ve seen plenty of cases where scripts under /etc/profile.d ended up creating massively long environment variables as well because of this problem (it’s not just a problem for the PATH environment variable). And what if I place a script under /etc/profile.d that does something like a file system mount? Would I potentially end up with infinite mounts on top of each other? Would I have to wait on the mount to complete every time a bash shell gets spawned?

What if, for efficiency’s sake, I want to spawn a bash login shell with the just the minimal login environment defined, but I don’t want to run all the start-up scripts that every installed program has dropped under the /etc directory? From the documentation, it would seem like bash –norc ought to do that, but the way everything is sourced (multiple times) from everything else, it appears that that option to the bash command is completely meaningless at this time.

I think a much cleaner design would be to simply source ~/.bash_profile once on bash login shells (falling back to /etc/profile if that doesn’t exist). And to always source ~/.bashrc (falling back to /etc/bashrc if that doesn’t exist). ~/.bash_profile should be for stuff that should only be run once and ~/.bashrc should be stuff that should be run every time.

Just my two cents.

Stephen Snow

Hello Gregory,

Multiple sourcing is a poor practice, and there is a check in /etc/bashrc to prevent dual sourcing it but not in ~/.bashrc. I chose to present the tips as the GNU Bash manual indicates. For example, the documentation purposely shows alias’s and functions in /etc/bashrc and ~/.bashrc and this is noted in comments in the profile files /etc/profile and ~/.bash_profile as well.

From /etc/profile …

Stephen

Gregory Bartholomew

Yeah, those comments seem inaccurate at the least. If they were true, how would ~/.bash_profile and ~/.bashrc get called? I know they aren’t called from the global scripts.

That check for double sourcing appears unreliable/bogus too. What if I run “bash –login” followed by “bash –login”? Since the only double sourcing check in done in /etc/bashrc, and since everything under /etc/profile.d is sourced from /etc/profile, all the scripts under /etc/profile.d will still get double sourced.

I suspect there should really be a /etc/bashrc.d in addition to /etc/profile.d so that there would be a cleaner divide between the two types of scripts rather than all the stuff under /etc/profile.d getting run many many many times over every time a bash script is run somewhere.

Again, just my two cents. There may well be some details of which I am unaware that make a cleaner divide between run-once and run-always scripts impractical.

Stephen Snow

The article was more about Bash than Fedora per se. I didn’t mean to give the impression that you should follow everything I typed there verbatim. In fact I would expect those interested to review the material, read the links to get more informed, then customize their system to their own needs. What I was trying to get across specifically was the order of startup, what files are or could be accessed then, and how might you do some customization to suit your workflow and use case needs.

George N. White III

In these days of projects with participants spread across multiple organizations and using different linux distros it is worth mentioning a common source of confusion when fedora users interact with debian/Ubuntu or macOS users. It is helpful to realize that users of other distros may have dash (default system shell on debian) or zsh (default user shell on recent macOS).

Stephen Snow

Hello, and thank you for noting there are different default shells in use by other Linux Distro’s as well as Mac’s. I had originally opened this article stating that there is a large variety of choice of shell to use even in Fedora, but the focus would be on Bash, and it’s use within the context of a Fedora system. The broader topic of different shells, and their relative benefits/drawbacks would be a rather large (amount of) content (for a magazine article) if you wanted to attempt to do the topic justice. It would likely need to be a multi-part series. Generally, as a preference, I use zsh on my Fedora system. For this article and some time leading up to it, I have been using Bash.

John

Please correct me if I’m wrong but in Wayland the ‘profile’ scripts are no longer sourced.

Stephen Snow

Hello John,

You are likely referring to the discussion around this https://ask.fedoraproject.org/t/ld-library-path-is-not-set-by-bash-profile-anymore-after-upgrade-to-fedora-31/4247/13. In particular, this is relevant in how the startup scripts are processed, and in fact if they are processed as expected in the first place. The article is written from the POV of the Bash manual, so there are certain expectations on the startup behavior and the subsequent behavior of the shell. Specifically, that the distro is following the suggested sequence of login and startup for processing the environment scripts. This is not so clear cut now with Fedora as of F31, since for instance the Gnome Session is now managed by systemd(https://blogs.gnome.org/benzea/2019/10/01/gnome-3-34-is-now-managed-using-systemd/). So the ~/.bash_profile file is sourced (for now, but this may change) and for the interactive terminal sessions ~/.bashrc is still sourced.

Gregory Bartholomew

For anyone who might be interested, I’ve found that an easy way to block a lot of the double sourcing is to add the following line to /etc/profile.d/sh.local:

The above will block /etc/bashrc from ever being run, however, so if you use it, you will need to duplicate anything in /etc/bashrc that you want in your ~/.bashrc. For me, this amounted to the following:

You want to keep ~/.bashrc very minimal because everything in it is run every time bash is executed (without the –norc parameter).

I’ve also tweaked my ~/.bash_profile and added a /etc/profile.d/ps1.sh to set the bash prompt for login shells. The end result of editing these four files is that now when I run just bash (or when a bash script is run), there is no chance that any of the content under /etc/profile.d will be re-evaluated. This is easily verified because spawning a non-login bash shell reveils the default bash prompt (because /etc/profile.d/ps1.sh was not sourced). Below are the four files I’ve changed in their entirety. This is just an experiment at this time, so there may be problems with this setup that I have not noticed yet.

/etc/profile.d/sh.local

/etc/profile.d/ps1.sh

~/.bash_profile

~/.bashrc

I’ve also set gnome-terminal to always run bash as a login shell. This makes sense because the shell that gnome-terminal starts is never the child process of another bash shell — it cannot inherit an already initialized bash environment, so it needs to be run as login shell each time.

Robin Meade

Cool! Thanks for writing that up.

I don’t find the need to set gnome-terminal to always run bash as a login shell. On my system, gnome-session is run by a bash login shell. My process table shows:

I do need to log out and back in for changes to my .bash_profile to take effect; that’s the only downside I see to not setting gnome-terminal to always run bash as a login shell.

Gregory Bartholomew

Yeah, it looks like you have a somewhat non-standard setup there where gnome-session is a child process of a bash login shell.

I think your best option to get around having to logout and back in in that case would be to create something like ~/.gnome-terminal that ends with “exec bash”. Then set as a custom command for gnome-terminal something like:

/bin/bash -c “source $HOME/.gnome-terminal”

instead of your login shell. I haven’t tested such a setup, but it should give your a third option for where you can place configuration settings that would not require you to log out and back in (and also would not get run every time bash is run).

Just an idea,

gb

Gregory Bartholomew

Just realized that you should probably check for the existence of the file first, so maybe something more like:

And if you want to eliminate the requirement that ~/.gnome-terminal end in “exec bash”, maybe something like:

Robin Meade

OK, thanks Gregory. I was running Gnome using X. But with Wayland, bash is still executed as a login shell when gnome-session starts. See https://gitlab.gnome.org/GNOME/gnome-session/-/blob/master/gnome-session/gnome-session.in Anyway, I’m OK with needing to log out and back into my Gnome session to pick-up any changes to environment variables that I set in my ~/.bash_profile.

Gregory Bartholomew

Interesting. I too now see that gnome-session is listed as being spawned from a bash login shell. However, experiments suggest that gnome-terminal is not a child of that bash login shell. I still have to set gnome-terminal to run bash as a login shell to get the content under /etc/profile.d processed (e.g. PS1) with my setup.

What I can make of the output of pstree seems to suggest that gnome-terminal is being spawned directly from systemd somehow (or perhaps from DBus as the article Steven linked earlier suggests).

smeagol

export HISTTIMEFORMAT=”%m/%d/%y %H:%M:%S ”

^^ this is what I use. Do you like it? Can it be improved upon?